Something I have learned perhaps too late in my life is the old saying that, “If the map and the ground disagree, the map is wrong.” There are a lot of different ways to translate and apply this, but mine is that usually, what everyone says or think or believes about a thing is often nonsense. Conventional wisdom, in other words, is usually wrong. When you’re actually in the place, doing the thing, firsthand, you find out that what you’ve heard, often from many directions and for a long, long time, is utter bullshit. The real story is completely different.

A simple example is childbirth. I was present for the birth of all three of my daughters. Since two of them were twins, and C-sections, and thanks to my genetics, I make huge babies, the delivery room looked like an abattoir when it was all over. But I digress.

For a parent, childbirth is supposed to be some kind of miraculous moment of transcendent love and beauty. Everyone says so, right? I have read about the rush of love and connection the appearance of your offspring is supposed to engender.

Well, it doesn’t. Having been actually there, I realize that it was about as transcendent as getting your oil changed. All I remember is feeling very, very tired. I can’t imagine how my now ex-wife felt, except she got a lot of drugs and a string of museum-quality pearls in the bargain, both of which I assume helped ease any discomfort.

The transcendent parental moments came later, during the course of everyday life. I remember watching one of my daughters act in a school play and starting to cry, to the point that another daughter looked over at me and said, “Dad, are you okay?” Or reading something another had written as her college thesis, and being shocked by how good it was. As a writer, when it turns out that each of your daughters has turned out to be both a reader and a writer (one professionally) you have definitely transcended. A little piece of you is, in fact, in them.

Another example of the map/ground issue is the little town I grew up in, Corning, New York. The town itself is tiny, with a population of around 11,000 people. It is also absolutely dominated by Corning, Inc., a Fortune 500 technology company with around $12 billion in annual revenues, and operations all over the world. Among other things, Corning invented and manufactures the optical fiber that makes the Internet work, and Gorilla Glass, which is probably on the faceplate of your mobile phone.

As a result, the city of Corning is a classic company town. You can read endlessly online about “late-stage capitalism” and the horrors of corporations, especially if you read lefty publications. It’s also easy to read about what stultifying traps of oppression, racism, mediocrity, cruelty and boredom small towns are. People who know nothing about them usually write this kind of shit.

One of my favorites is the old Simon & Garfunkel tune, “My Little Town”, written by Paul Simon, who, of course, grew up in New York City:

And after it rains there's a rainbow

And all of the colors are black

It's not that the colors aren't there

It's just imagination they lack

Everything's the same back in my little town

Nothing but the dead and dying back in my little town

This. Is. Complete. Faux-Sensitive. Bullshit.

My upbringing is evidence. I love my little town, and the older I get, the more I recognize how remarkable it was. Corning was, and is, is a wonderful place, and it’s all because the corporate overlords in charge, the ones who were supposed to have their feet on the necks of the peasants, were in fact careful, smart and responsible. The image of the cruel, greedy capitalist laying waste to the good, hardworking citizens of a small town is ridiculous.

To make the paternalistic company town angle even more compelling, not only was Corning (the company) dominant in the town, but it was also, for most of its history, a family business. That family was the Houghtons, many of whom I knew. Quincy Houghton was my seventh-grade girlfriend, as a matter of fact, before she headed off to boarding school. I have learned, over the ensuring fifty years, to accept the fact that our romance never would have worked out. I’m a writer and she’s an … heiress.

Anyway, along with being industrialists, capitalists, patricians and insanely wealthy, the Houghtons, as a group, were also responsible for a thriving small town, a very successful company, and making the lives of thousands and thousands of people much, much better.

Corning has been in Corning since the middle of the nineteenth century. The company was relocated to upstate New York from Brooklyn, and started out making, I think, glass for railroad lanterns. Then, in the early twentieth century, they developed a way to manufacture light bulbs for Thomas Edison, who you may have heard of. There was always a heavy emphasis on research and technology, and through the decades, the company developed and manufactured a lot of things people use every day, but don’t think about – Pyrex cookware. Television tubes, back then people had televisions. Catalytic converters, which remove pollutants from tailpipe emissions in cars. And again, more recently, faceplates for mobile devices, and optical waveguides.

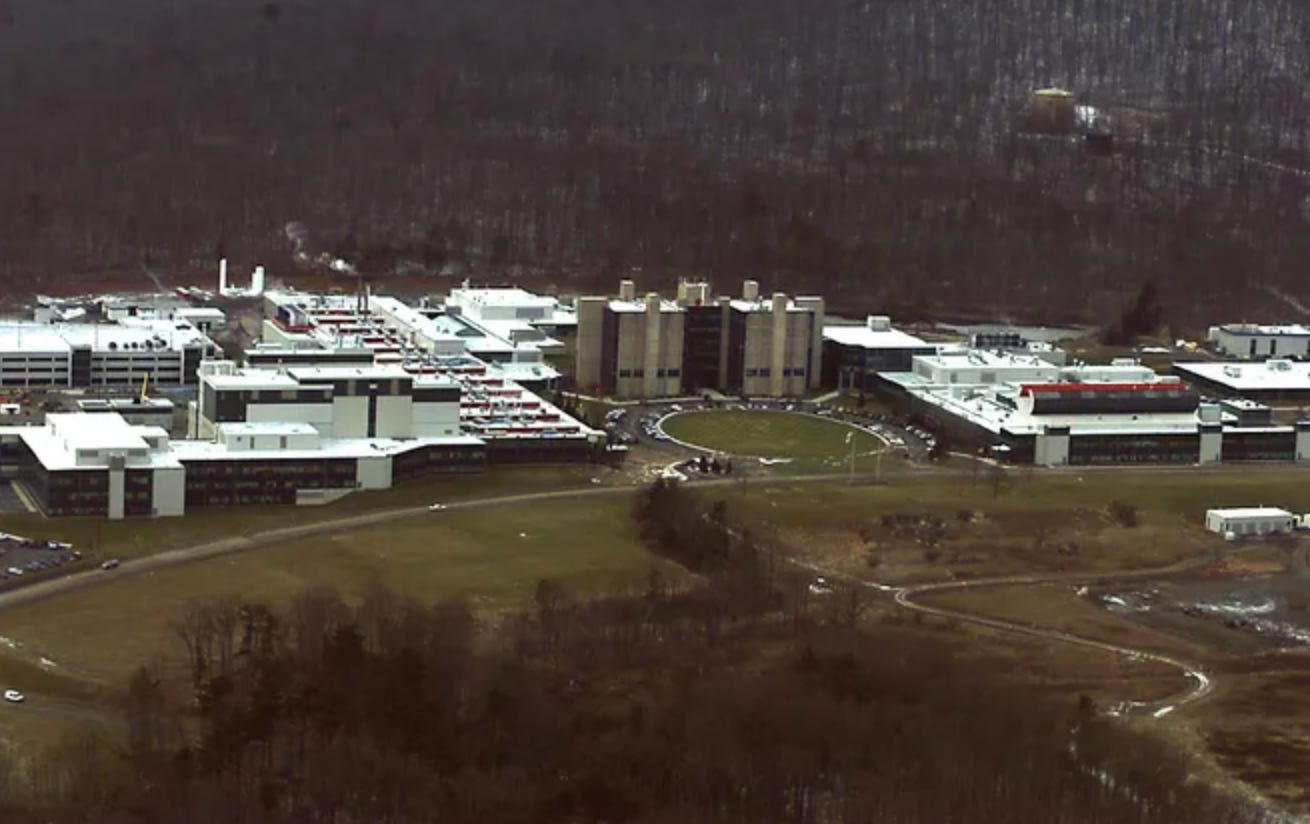

Headquarters for Corning’s R&D was (and is) Sullivan Park, a massive (2 million square feet) research complex located on a hilltop about five minutes from the house I grew up in. I remember seeing a calculator for the first time there. My friend’s father was a chemical engineer there, and one night, after work, took we two boys to see his amazing new device. It was about the size of a microwave oven, had a glass screen, and could multiply, add, divide, subtract and take square roots. We spent an hour just playing with it. Now, this much capability is baked into our cell phones as a kind of digital afterthought.

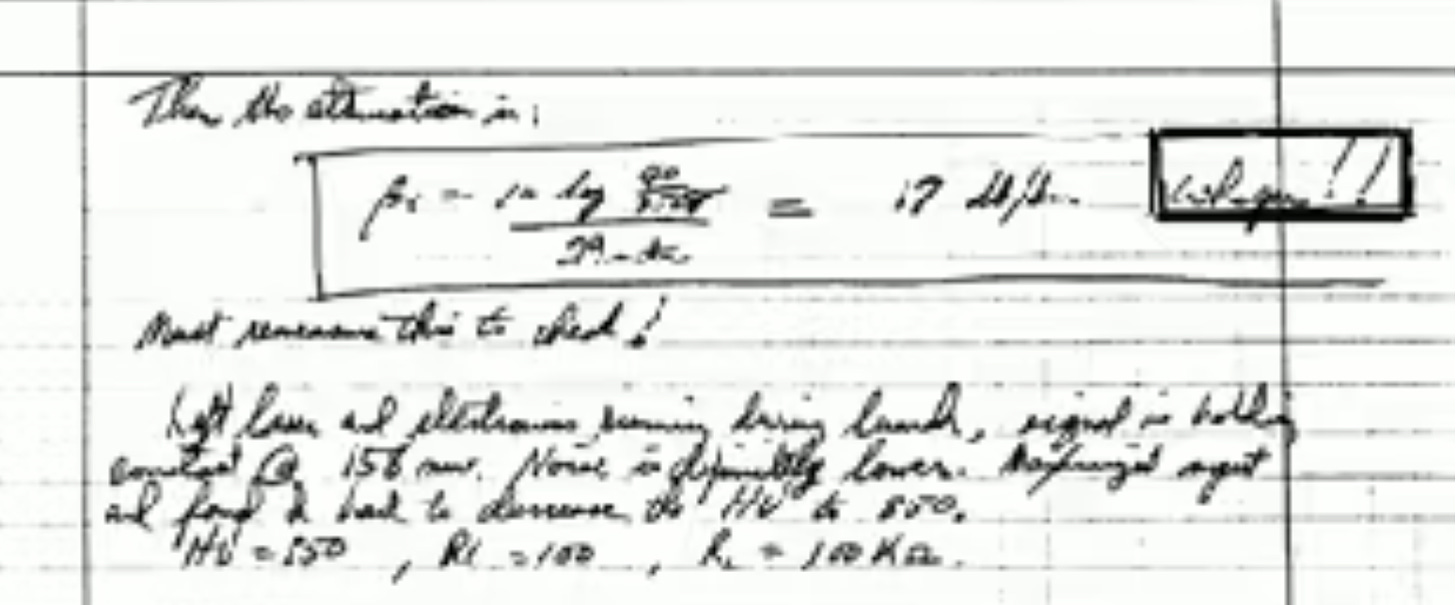

Corning also invented optical waveguides. These are hair-thin strands of extremely pure glass that allow huge amounts of data to be transmitted very long distances using lasers. One strand of this stuff can carry as much information as a thick copper wire, and carry it much further and much faster. Basically, the reason everyone can watch Huak Too Girl videos is that Corning developed a way to get unbelievable amounts of data where it needs to go at literally the speed of light. The lab notebook of the team that developed the first commercially viable optical waveguide is now in the Smithsonian, with the amusing comment “Whoopee!” in the margin for the day they made it work. There aren’t many times that you can see evidence of exactly how, when and why the world changed, but that notebook is one.

It’s also a perfect example of the town/company relationship I’m describing. One of the guys who developed this stuff was a fellow named Peter Schultz. I went to high school with his daughter. In my little town, the senior business people and the day-to-day townspeople lived together and worked together. Another great example of this is Ann Marie Ruocco and her husband, Clark Kinlin.

Corning (the town) is home to a lot of Italian and Irish families that have been there for generations. The Ruoccos are a perfect example. Everyone went to high school with one of them – a cousin, a sister, or something. One branch of the family operated Aniello’s, the local pizza place which still, for my money, has the best pizza on the planet. Ann Marie ran the place day-to-day. I had a massive crush on her in high school – she looked like a Roman goddess – but I was way too shy to speak to her.

Decades later, I was in an elevator in a hotel in Venice, and a group of middle-aged Italian women, dressed to the nines for a formal wedding reception, got on. They were regal, dignified, and heart-stoppingly gorgeous. And I thought of her.

Fittingly, she ended up being asked out, marrying and having a family with a senior Corning executive with a Harvard MBA. She’s now still runs Aniello’s, but is also a collector of art glass, and has a very elegant second home in the Finger Lakes region of New York. And she still makes pizza, and looks like a Roman goddess, albeit one with silver hair.

Physically, the town’s layout is that of a classic American industrial town as well. The factories, and the company offices, are down on the river. As one got further up the hill from the river, the houses got bigger and nicer, and near the top was where the executives lived. Because it’s such a small town, Sixth Street was the top of the hill. At the very, very top was The Knoll, which was the redoubt of Amory Houghton Sr., or “the Ambassador”.

The Knoll was, basically, a mansion. Built in 1917, it covered 13,000 square feet, on five acres of land, surrounded by an iron fence. Here is a description of dinner there:

It was called The Knoll, a name which appeared in red letters on neat stacks of stationery in every bedroom, but principally on pads of paper in the room called “the telephone room.”

A maid whisked my suitcase away to unpack my things and to press not only my dress for dinner that night, but also my nylon stockings. Jamie’s mother met us in the high-ceilinged library where John Law, the longtime butler—almost a family member, though remote and disdainful in his uniform of dark jacket and striped trousers—carried in the tea tray…

That night at dinner Mr. Houghton appeared in a red velvet smoking jacket and John (by now in tails!) passed another tray at the end of the roast beef meal. This time it was cigars and cigarettes laid out on a silver platter. The flame of the torch-like lighter attached to the tray was already lit, so one only had to slightly nod in the direction of the lighter to start one’s smoke. Mrs. Houghton took one puff of her cigarette, then crushed it out on one of the Steuben glass ashtrays in front of each place.

The Ambassador, as he was known, was a huge friend of my father’s, who was his physician, contemporary and confidante. If anyone personified a capitalist apex predator, it was he. Educated at St. Paul’s and Harvard, he was a friend of Eisenhower, Chairman of Corning (the company) for twenty years, Ambassador to France, and related to a ridiculously long list of prominent Americans of the twentieth century – Katherine Hepburn and Alice Tully among them. They also, by the way, donated the Houghton Library to Harvard, among other things.

Which leads us to the best, final story, which is that of Amo Houghton’s dog. Every word of what I am about to relate is true.

At one point, Corning had dozens of bars and taverns on the main commercial street, Market Street. Manufacturing with glass is very hot, loud work. Glass melts at about 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit, and is cooled with compressed air. A television tube manufacturing line is kind of a version of hell. Consequently, during breaks and after work, the men who worked on the line were very thirsty, and there were numerous joints set up on Market Street to help them out. In some of these places, people had regular seats, and their regular order would be waiting for them when the factory whistle blew. Someone would get off work, and at their appointed seat would be, say, two beers and a shot.

Amo Houghton was the Ambassador’s son, and the heir apparent to leadership of Corning (the company). He was CEO and Chairman of the Board from 1963 until 1984. Interestingly, Amo and I shared a birthday, and he was kind of a distant, benign advisor and role model. After my own father died, I talked to Amo first, and he was also a major part of why my sister Molly eventually became a priest.

Anyway, Amo lived in an enormous house on Third Street, and owned a basset hound named Henry. Several nights a week, Henry would get out of the house after dinner, head down to Market Street, and start hitting the taverns.

The bartenders all knew him, and were happy to provide him with beer. The last stop of his evening was usually the Steuben House, where the bartender, Tut Heverly, had a special bed for him. He was literally a dog about town, and when the party was over, he would be brought home to Amo’s house by either the Corning cops or the local taxi service. Being a dog, he was not in the least ashamed of his lifestyle.

I have traveled, and lived, all over the world. Although I’m not done yet, I have been to Singapore, Seoul, Hong Kong, London, as well as pretty much every major city in the US, including Dallas. I hate Dallas. I also hate Los Angeles. I don’t think much of Houston, either.

Anyway, when it comes to places to live I think I’ve seen every party clown there is. And as I wrote in a previous Substack, unlike a lot of people I’m also from somewhere. I’m from Corning. I was, as the song goes, born in a small town, and as the song also suggests, that’s probably where I’m going to be buried.

There is a tendency for writers, in frantic pursuit of status, to depict small towns as either Ground Zero for evil, or endlessly tedious and irrelevant, or populated by Colorful Local Characters who the writer subtly (or unsubtly) depicts as being sort of stupid. That’s the map. This condescending criticism is a lot more pronounced when you stir into the mix the presence of a big company. Literary types clap like seals performing for fish at negative descriptions of small towns. Sinclair Lewis, who by all accounts was a miserable human being, made a career out of this.

The ground is different. My little town was, and I assume still is, populated by smart, caring, tough people, good people. It’s a place where the past is respected and protected, where business is done and innovation’s alive and well, where a dairy farmer will stand in line at the grocery store right in front of the Senior Vice-President for Strategy for a Fortune 500 company. There is no place in the world that’s an unmixed blessing. But my little town comes close.

Peter, a great article about our shared hometown. We were extremely lucky to have grown up there during the years we did.

On another note, I believe our fathers were colleagues. My father was Dr. John G. Allen. He was one of the two OB/GYN’s in town during those days.