A few months ago, I was sitting in the office of my pal Marty Ennulat, shooting the breeze, as they say. I’d brought the Handsome Boy, who was leaping around with Marty’s dog, but since it was Marty’s office and no clients were present, the chaos was amusing rather than distressing. Then, in the slipstream of our conversation, I heard two words that surprised me.

Ball season.

I interrupted him. “Wait, what? What do you mean, ball season?”

“Well, there’s the Blue Moon Ball in January. There’s the Valentine’s Ball in February.”

“Here?”

“Yes, here. Every year.”

I had just moved back home from California, I knew about none of these events, but I decided then and there that I was absolutely not going to sit them out.

I need a tuxedo.

Corning is an absolutely amazing little town. Although my roots here are very, very deep, I’d also been on the West Coast for the last 25 years, and had some catching up to do. It turns out that formal, black-tie events are a thing here — still.

Writers, of course, are not supposed to like social events. Think of Emily Dickinson, holed up in her house or, God help us, her bedroom. In fact, Billy Collins wrote a wonderful little poem unsubtly entitled Taking Off Emily Dickinson’s Clothes in which he imagines seducing her. Think of Thoreau retreating to Walden. Or the king of them all, Marcel Proust, hiding in his cork-lined room and producing 4,215 pages of À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. Which is actually a pretty dumb title, because if you remember something, by definition it happened in the past. You can’t exactly call your masterpiece Remembrance of Things That Haven’t Happened Yet, can you?

But unlike these people, I absolutely love parties. I love the energy, the excitement, that sensation of crossing the threshold into a room full of people. I actually keep a mental list of the very best parties I’ve ever been to1. In fact, in college, I wrote a newspaper column for a few weeks in which I reviewed parties, as if they were movies. That ended quickly, as, for instance, describing someone’s event as only for the “drunk and the desperate” tends to make enemies.

And as I’ve written about elsewhere, I’m not a stranger to black tie. In college, I was one of the hosts of the infamous Champagne party, which was both great fun and incredibly destructive. More recently, I attended a niece’s black-tie wedding at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, one of the nation’s great museums. Like most sane people of a certain age, I now really hate attending weddings, but this one was different.

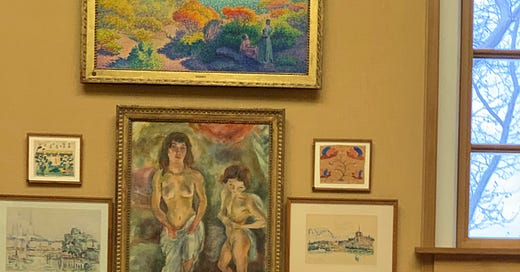

First, they’d rented out the entire museum. Along with the music and the drinks and the food, you could wander around the place, at least for the cocktail reception part of the proceedings. The instant my date learned that the galleries would be open to wedding guests for an hour, she handed me her drink and vanished. It was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to stand alone in a room with Renoirs, Matisses and Picassos. Who could blame her?

Second, I was seated at the same table as the President of Dartmouth, and having had a couple of drinks, I felt free to lean across the asparagus, to paraphrase John Kennedy, and ask him why Dartmouth didn’t admit me … back in 1980. I always wanted to make the colleges that dinged me explain themselves, and this was my chance. Given that he makes his living attending events, essentially, his response was very smooth.

When I was growing up in Corning, the big black-tie event was the Hope Ball, presided over by the formidable Laura Richardson Houghton2. The money from this event, which, of course, Laura could simply have written a check for, was, to quote her New York Times obituary, for “Project Hope, the international medical education and training program, which operated a hospital ship, the S.S. Hope.”

Pretty much everyone in town went. This was a chance for machinists and laborers and bookkeepers and their wives to put on the dog, and attend that same social event as the regal Houghtons. My father had a tuxedo, my mother had a mink, and if memory serves, off they would go. Laura Houghton lived to be 102, was the very definition of “matriarch” and probably saw the ball as a community-builder as well as a fund-raiser. She wasn’t wrong.

Because it’s the headquarters of a $14 billion technology company, there is a lot of money and sophistication in Corning, despite the fact that it’s a small town in the middle of, essentially, nowhere. And I mean nowhere.

Shortly after moving here, I remember standing in the parking lot of my building one windy winter night. The ground was covered with snow. And I was suddenly struck with this powerful feeling of being in the middle of absolutely fucking nowhere. The sense of remoteness hit me like a cinderblock dropped from a helicopter. This brave little town was tucked into a river valley, but in every direction was basically frozen emptiness for miles and miles and miles.

To the west, it was 150 miles to Jamestown and the Ohio border, and in between were just a lot of little hamlets (if that isn’t redundant) and the Allegany Indian Reservation. To the south were the mountains of Northern Pennsylvania — really empty. To the north were the Finger Lakes, and western New York — more empty. And to the east were the bustling metropolii of Horseheads, Elmira, and then much nothing until you hit Binghamton. And in the middle of all this was a sophisticated, prosperous little town, Western New York’s Brigadoon, that held black-tie events in the winter. For which one needs a tuxedo.

Here’s what’s cool about tuxedos, or if you’re British, dinner jackets. No matter who you are, no matter how you’re shaped, no matter what you actually look like, a tuxedo makes a man look elegant. Really. It’s amazing that way. If you’re short, or fat, or bald or otherwise weirdly built, somehow a tuxedo makes it irrelevant. And if you’re tall and broad-shouldered — ahem — they make you look amazing.

It’s also a much more complicated garment than anything else a man wears. A tuxedo includes:

Black patent-leather shoes. Polished to a mirror-like finish and absolutely absurd in any other setting, these babies look great with a tuxedo, and ridiculous everywhere else.

The jacket. A tuxedo jacket is all about the lapel. There are peaked lapels, shawl lapels and a bunch of different variations on the basic theme.

The bow tie. Black only, no matter what. I take a firm stand against wearing madras bow ties or any other absurdity.

Pants. Held up with suspenders (or braces, to again quote the Brits), with a silk stripe down the side in a relatively muted color.

The shirt. Can have pleats or a plain front. White only. Instead of buttons, you use studs. And cufflinks, which are a pain in the ass but look great.

The cummerbund. This is a strip of pleated fabric (pleats facing up only, to hold your opera tickets) around your waist which beautifully hides your belly, should you have one.

Okay. Let me interrupt this for a vital second. Whoever you are, wherever you are, because I love and respect you, I’m going to now do something so rawly honest, so sincere and so brave that your eyes are going to fill with big, fat tears. I’m going to show you the first time I ever wore a tuxedo. If being a writer is all about relentlessly trying to share the truth, here’s some truth for you. Joan Didion said once that writers are always selling someone out. I’m going to sell myself out. Right now.

My high-school prom. And the famous Brown Tuxedo. Behold:

That was the absolute epitome of style in Steuben County, New York, in 1980. What a figure I cut, huh? To be honest, of course, I look like a white boy auditioning for The Temptations.

Okay. Back to the real world.

Along with being complicated, and looking great, a tuxedo also is perhaps the most romantic garment a man can wear. It puts you, and them (i.e. women) in mind of James Bond (who I’ll get back to in a bit). The symphony. Silver cigarette cases. Elegant dinner parties. Panache, joie de vivre, rakish elan and a certain je ne sais quoi, all wrapped up in one formally-dressed package.

Combined with champagne, or at least a drink or two, it transforms you. With a tuxedo on, you are suddenly aristocratic, polished, a man of substance and experience with an undercurrent of dashing irreverence. You are the kind of guy who will toss back a Martini and then teach the vulgarian who has the bad judgment to mess with you a thing or two while your date swoons.

The very best example of this comes from one of the greatest and most difficult books I’ve ever read. Which requires yet another story. Actually, two stories.

Story One: When I lived in Santa Cruz, California, I became acquainted with a retired professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz named Paul Lee, who has since died. Paul had been a high-profile professor of theology and, God help me, History of Consciousness — whatever that is. He was one of the resident intellectuals of the counterculture there, was very well paid, and also managed to piss off enough members of his department that, I believe, he never got tenure. Or resigned. Or something. When I knew him, he was elderly, enormous, and used to occasionally lecture dressed up like the Harbinger, that character in the John Wick movies who oversees the duel.

Paul also had Martini parties every Friday afternoon featuring weapons-grade cocktails, enough food to feed an army, and a constantly shifting cast of intellectual pals, hippies, friends and family members. He had a beautiful, enormous house, and attendance at one of his parties pretty much guaranteed that you would depart barely able to stand, but having had a great deal of absolutely fascinating conversation. I loved Paul’s parties. He was a legendary host. Hell, he was legendary in general.

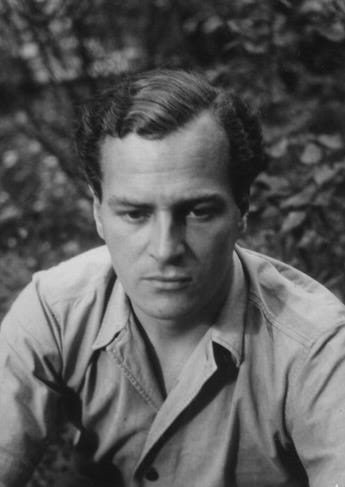

At one of these, he mentioned an author. I was alert enough, incredibly, to pay attention despite all the gin, remember the name, follow up, and discover Patrick Leigh Fermor. I now have sort of a literary crush on him.

Story Two: Fermor was, to put it politely, uncooperative. He graduated from Oxford, I think, and was insanely brilliant and ridiculously talented, but unfortunately, not rich. He absolutely did not want to go and get a job like a good little Brit. What he wanted was adventure, which was what pretty much defined his life. Later in life, this guy literally kidnapped a Nazi general during World War II and snuck him out of Greece and back to England through thousands of Germans hunting for him. Among many other accomplishments, he is said, truly, to have been the inspiration for James Bond. So what did he do, diploma in hand?

He took a steamer to Rotterdam, and then walked to what was then Constantinople, now Istanbul. In other words, across all of Europe, North to South. He, of course, was, ah, temporarily impecunious, but what he did possess was an absolutely mind-bending level of erudition, an iron constitution, and ceaseless charm. While some nights were spent sleeping in ditches, many others were spent being put up by what seems like an endless list of aristocrats in places like Romania. These people would provide him with food, lodging, introductions to their aristocratic friends, and when necessary, dinner jackets.

Fermor made his trek between the World Wars, and encountered the last vestiges of a society Hitler was about to burn to the ground. Dinners and shooting and parties and picnics with beautiful, sad, doomed countesses and barons and lords whose centuries-old time was just about up because here comes the Wehrmacht. And in one of these places, during one of these encounters, after yet another beautiful alcohol-fueled evening with yet another member of the fading nobility, he wrote the best, most enticing example of what a tuxedo is for I’ve ever read:

When a mid-morning sunbeam prized one eyelid open a few days later, I couldn't think where I was. An aroma of coffee and croissants was afloat under a vaulted ceiling; furniture gleamed with beeswax and elbow-grease; books ascended in hundreds, and across the arms of a chair embroidered with a blue rampant lion with a forked tail and a scarlet tongue, a dinner jacket was untidily thrown. An evening tie hung from the looking glass, pumps lay in different corners, the crumpled torso of a stiff shirt (still worn with a black tie in those days) gesticulated desperately across the carpet and borrowed links glittered in the cuffs. The sight of all this alien plumage, so unlike the travel-stained heap that normally met my waking eyes, was a sequence of conundrums. Then, suddenly, illumination came. I was in Budapest.

And that is why I need a tuxedo.

It was the Bay Area French-American Chamber of Commerce’s annual soiree, which filled the entire Sony Metreon in downtown San Francisco, and featured three floors of basically endless food and wine from every French vendor in the city, as well as fascinating actors roaming around in full costume and makeup portraying assorted wild animals, like giraffes.

Interestingly, if you Google “Laura Richardson Houghton” you come up with very few images, despite her long life, wealth and prominence. Why? Well, because people of her social circle believed that your name should appear in the newspaper only three times — when you were born, when you married, and when you die. And maybe not even then.

Disagree about the ties. I have many ties, some with matching cummerbunds, of many different patterns and colors. Variety is key. Also, you omitted waistcoats, always a popular alternative to cummerbunds (and with their own ticket pockets). I have waistcoats of different patterns, including one (with matching tie) from my Oxford Uni dining society, the Stoics: royal blue with sunflower yellow lapels, and of course brass buttons with society logo inscribed.

I remember my parents attending the Hope Ball and they always had a cocktail party at our house before hand.