One of the most consequential thoughts I’ve had lately is also one of the most simple, obvious and ancient: I am going to die. Welcome to this week’s Specific.

Last week, I wrote about my mother. She died in 2022. I have a photo, which I will not share here, one of her caregivers took of her on her deathbed. The women who do this work are incredible – they literally tend to the dying. In the photo, my mother is on her back, with her eyes closed. Her hair has been brushed. She’s wearing lipstick and makeup. She’s fully dressed. And she has only hours left to live.

Towards the end of her life, I cultivated the habit of sending her pictures every day from wherever I happened to be, and whatever I happened to be doing. I think one of the real horrors of old age is being isolated from day-to-day life, so I sent her pictures to try to remind her that she was still alive, still connected, still part of the ongoing story of the people around her.

The last set I sent her were from a beautiful little cove in Point Lobos, on Monterey Bay, where we had gone hiking. The place is called The Pit, and it’s a lovely spot, secluded and kind of magical. We snuck in by climbing some cliffs at the end of a public beach, then hiking down the coast. That night, or the next day, she gradually lost consciousness, and the process of dying began. She simply didn’t wake up.

She is now with my father in Lakewood Cemetery, in Jamestown, New York, by Chautauqua Lake. My sister Molly handled the incredibly thankless task of clearing out her house. The house was sold. Her estate was distributed. Eventually, every trace of her was gone.

And the thinking began. I am now alone. The last of her generation is gone, and my generation is next – including me. This happens to every living creature on the planet, and now it’s happening to me.

I have a will on my wall from one of my ancestors, written two centuries ago. The language is remarkable, elegant and powerful. One of the sentences reads: “It is appointed to all men once to die.” Truer, righter words have never been spoken. He died. My mother died. I’m going to die. And so are you. That moment is going to come when it’s time for it all to be over. I think the purpose of life, at least in part, is to get ready for that moment.

Everyone realizes this on an intellectual level, of course, but when the last parent passes away, it really, really sinks in.

The central concept, the main, irrefutable idea that’s arisen for me is that this story I’m in that I call my life definitely has an end date, and it’s coming. I do not have forever, and there will come a day – really – when there will be nothing more said, or thought, or experienced, or learned. I will have done what I’ve done with this life I’ve been given, and that will be that. The story will end, the credits will roll, and then the lights will come up in the theater, everyone will file out into the evening, and go on with their lives. Except me.

I won’t be around to see it, or hear about it, or care. All the things that I am so immersed in now, as a human being alive in the world, will proceed without me. I’ll be on to whatever comes next, if anything. Hemingway (I think) wrote once that at the end, all an animal cares about is itself and its dying. Children, people you love, the work you did, the hopes you had, all of it will become irrelevant. It seems impossible that a moment will come when I won’t care about my children anymore. But it will.

One of the effects of this line of thought is that it gives you permission to stop caring about all kinds of things. For example, I find myself caring less and less about my reputation, my personal brand if you will, because in twenty-five years or so, I’ll be gone, too. That’s not a lot of time. I don’t go around being an asshole – I think -- but if someone decides they don’t like me, or what I do, a real, true, fact is that within a span of time I can conceptualize, it won’t matter because I won’t be here.

This, I think, is part of life’s natural trajectory. Children are surrounded by people whose opinion and behavior matter very much. In fact, for the first years of your life, it’s life-and-death. Abandoned children perish. As you grow older, different people – bosses, girlfriends, friends, teachers – enter the picture. We care what they think. And we accept their interpretations of things. If a teacher says something is silly or wrong or bad, we believe them, and often embed their point of view into our lives.

Patriotism, faith, gender roles, good and evil, beauty, money, sex, love – we’re told about all this stuff, we absorb what we’re told, and we then see the world that way, sometimes without realizing it. When I worked at Apple, I cared about the company, despite the fact that it had 350,000 people, and Tim Cook could trip over me and not know I was one of his employees.

But then we start to lose people. They age, they die, over and over and over. The beautiful woman who was a mentor, a force of nature and a guiding light becomes a hesitant, forgetful, frail old person with messy hair and too much makeup, sloppily applied. And the lesson gradually is learned – you’re on your own.

Nobody actually knows anything more about life than you do, and even more interestingly, the people who claim to are often liars, or grifters, or simply fools. You begin to rely on your own judgements and beliefs, because the people you once automatically believed turn out to be mortal, and then they’re gone.

Along the way, you start pruning back your attention. You care about less and less. Finally, I think near the very end of life, you cease to care about the world around you at all. I remember a few weeks before my father died, walking into the living room, and catching him gazing out the picture window. The sun was going down, the woods were illuminated by light, and the thought struck me that he was in the process of detaching, that in some way I couldn’t really explain, I knew he had already committed to the next place. He wasn’t here anymore. He was done. I could just tell.

Somewhere out there is a small piece of ground where what’s left of me will spend eternity. I think it’s going to be a small country cemetery near where I grew up, but I haven’t committed, so to speak, yet. It’s a beautiful place, quiet, with huge trees and surrounded by the hills I knew as a boy. Eventually, inevitably, everyone will forget that I’m there. My daughters will remember me, but their daughters may not, and their granddaughters certainly won’t. Whatever monument is put up where I lie will weather, and vanish. I think of that waiting hole in the ground from time to time. Older friends of mine have told me they think of their future resting place every day. It’s real. It’s really going to happen. It’s going to happen to me.

I think that during this, the final part of my life, it’s helpful to keep that place in mind. It puts a lot of things into perspective. The ancient Greeks called this a memento mori – a reminder of mortality. It translates as “Remember you must die.” I read a summary of this concept once: “Death twitches my ear and says, “Live. I am coming.””

Aging includes regular examples of this, a series of minor losses that are, I know, going to accumulate as I get older. I can’t really drink anymore. I need my sleep. Recovering from workouts can take a couple of days. My formerly steel-trap memory has a little sprinkling of rust. At some point, just as my mother did, I will need help to get out of a chair.

And instead of being a limitless timespan, with endless potential for adventure and change and experience – something I thrive on – my life now seems like a sponge that holds a certain, fixed amount of water. What can I wring out of it? Choices have to be made.

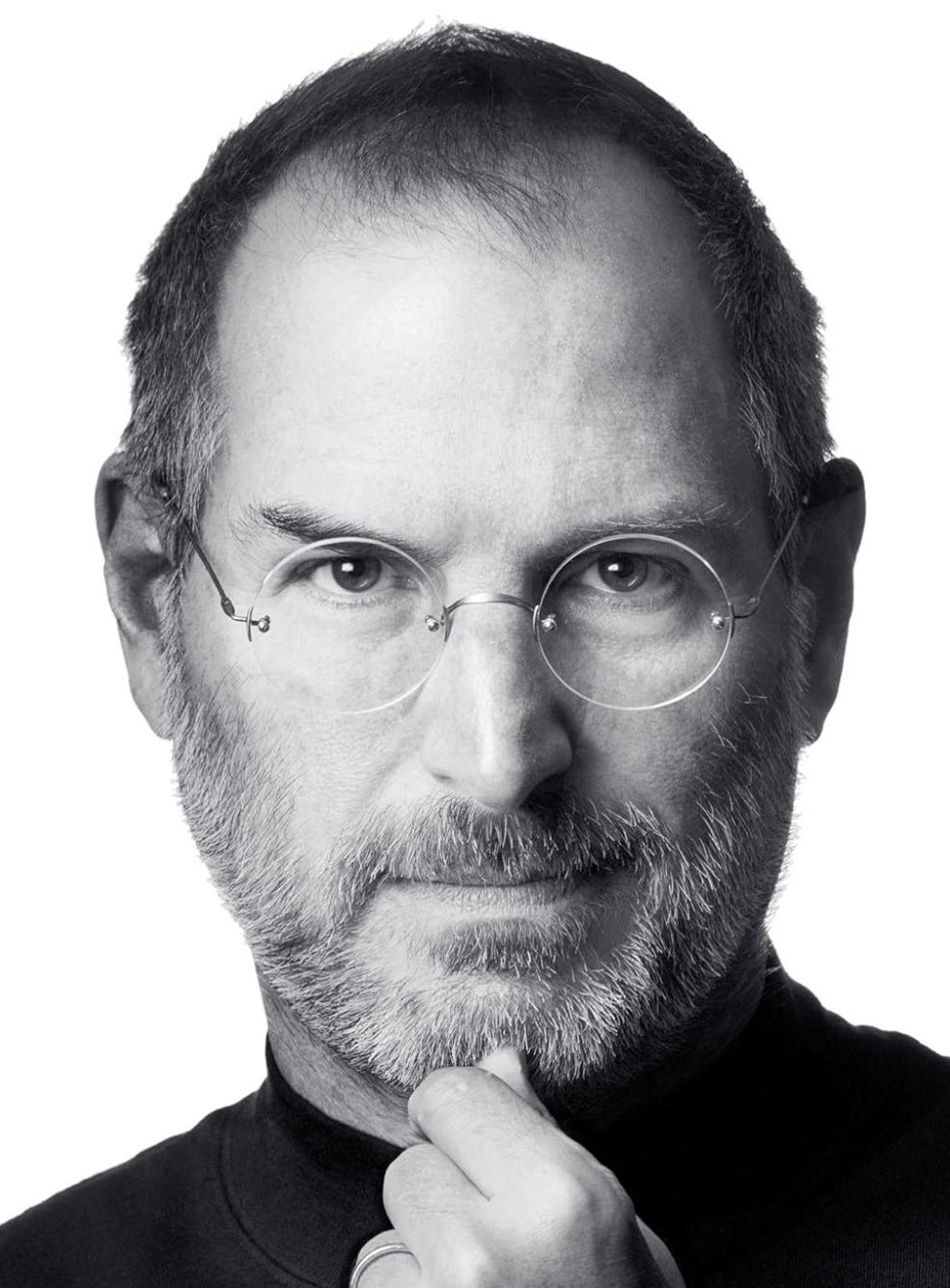

And, again, it seems to make less and less sense to care about a lot of things. Steve Jobs put it nicely: “Focusing is about saying no.” The latter part of one’s life, it turns out, is a time to focus.

I don’t care about the rise or fall of unions in the United States. I don’t care about Taylor Swift. I don’t care about trans rights. I don’t care about Gloria Steinem (who, incredibly, is still alive) or pirates in the Strait of Hormuz or the defense budget or the alleged effect of forever chemicals in the rain jacket I buy. I don’t care about Kate Middleton, or the effects of climate change on Greenland, or the ethics of Japanese internment camps in World War II.

So much of that stuff seems increasingly like white noise, pebbles in a can shaken in front of my face. As I wrote this, my phone, which is sitting on my desk next to my charging Apple Watch, a hang tag from Simms Fishing Products and my headphones, dinged to inform me of a piece about suicide rates among young adults.

The piece is larded with words like “imperative” and “urgency” and “mandate”. The writer, a “psychologist and author”, demands that I care. Off the top of my head, I can name four people I knew who killed themselves. One hanged herself. One blew his head off with a shotgun while watching hawks ride thermals. One shot himself in the head with a handgun. One, terminally ill, jumped from a window. They didn’t wait for death to arrive — they went out looking for it.

Suicide is horrible beyond belief – I know from personal experience. It doesn’t matter. In ten minutes, I could easily find twenty similar pieces, all demanding my attention, my money, my belief, my support. There’s always, always an ask. And at my age, this has been going on, with increasing intensity, for forty-plus years. I. No. Longer. Care. I have to prioritize. Focus.

I care about writing well, and getting better at it. Shorter sentences, taking more chances with topics, relying less on the Big Finish.

I care about how I feel when I get up in the morning, and why. Hint: get enough sleep.

I care about the people I care about – being a comfort to them when they need it, being a steady and reliable friend, being careful with my words, making sure they know how much they mean to me.

I care about figuring out how to fly fish from the beach effectively and safely – dealing with wind, waves, shifting sand and those stripers I’m chasing.

I care about that flickering flame of ambition and desire, and why it sometimes seems very low at 3 AM.

I care about doing everything I can now to ensure that my old age, assuming I get to have one, is as secure and healthy and peaceful as possible.

I care about keeping my day-to-day life running reasonably smoothly. We’re out of oatmeal, dish soap, Claritin. I have to figure out how to handle the grass that’s invading the garden. I need to redo the invoice for that law firm in Santa Monica.

But right now, Koda is jumping around in the back yard, barking and whining. He’s restless, and badly needs to be taken on a long walk. I’m going to oblige him. We’re going to tramp up and down hills. He’s going to cover himself in mud. I’m going to burn calories, think about writing, women, my daughters, the weather. And probably, for at least an instant, I’m going to think about that little cemetery, and the even smaller piece of it that will be mine.

Spot on. Wait ‘til you’re as old as I