A couple of years ago, I went to a dinner party at the home of Victor, a friend in Carmel, California. Victor is very gay, very charming, and is one of those guys people with $30 million houses in Jackson Hole hire to decorate it.

Two of the other guests were a married couple. The wife half of said couple worked at an organic farming company with some land on Carmel Valley Road. It’s important to note, by the way, that Carmel Valley is some of the most incredibly beautiful, expensive, coveted real estate in the country. Here’s what it looks like:

I’ve never been to Paradise, and I don’t anticipate an invitation anytime soon, but basically, it’s got to be Carmel Valley.

Anyway, we were standing in Victor’s kitchen chatting, and I was talking to said wife, whose name I’ve forgotten. She was telling us about her former career as a go-go dancer in San Francisco. She would arrive at gigs with her own cage, a solution to a problem I never thought of — the cages in which go-go dancers do their thing are kind of unwieldy, but hers, cleverly, could be disassembled and was therefore portable.

Polite dinner-party guest that I am, I then turned to her partner and said, “And what do you do?”

“I grow fava beans.”

At this point, my brain stopped working for a minute. I think I hid it pretty well, but every single red light on my mental dashboard started flashing. Gears started grinding. A voice with a thick German accent started screaming inside my head that something had gone drastically wrong. For what seemed like forever, I couldn’t figure out what to do with this information.

Nobody — NOBODY — makes enough of a living growing fava beans in Carmel Valley to survive. That’s like saying you live in the Hamptons and make pencils.

What the hell? What’s going on? The universe is dissolving!

Then I figured it out.

What we have here is a guy whose parents, or someone, made an enormous amount of money, which he now has some of. He has the trophy wife, a home in Carmel Valley, and since he doesn’t need to have, you know, a job, he amuses himself by cultivating fava beans, and pretending it’s a business. Okay. Right. Play along.

This kind of thing used to happen occasionally in California. And by the way, my dinner-party companions were perfectly nice, decent humans. I liked them both. And I learned something that night about both fava beans and go-go dancing, which isn’t something you can say about a typical dinner. But in California, people would frequently say or do things that demonstrated they had absolutely no idea how the real world operated.

As another example, shortly after moving to California, my then-wife and I were invited to a neighbor’s Christmas party. We went. Among the evening’s activities was sitting and listening to women in thousand-dollar holiday dresses talk about their homes in Tahoe in a fashion that made it clear that they thought owning such a second home — which, by the way, had a million-dollar price tag — wasn’t a big deal. Doesn’t everybody have a ski house in Tahoe?

I sat there and thought, “I went to high school with people who lived in trailers. A lot of people, in fact.” California took some getting used to.

I was thinking about all of this when I saw, on social media, something commanding me to boycott Wal-Mart last Friday, to teach them some kind of political lesson. You know, “hit them in the pocketbook.”

So, I went out to the Wal-Mart in Gang Mills, New York, where I grew up, and spent as much money as I possibly could. I managed to part with $177, which wasn’t easy.

I love Wal-Mart.

I. Love. Wal-Mart. I think it’s great. And the primary reason I love it is the customers.

Believe me when I tell you that the people who shop at my Wal-Mart, by and large, do not even know what a fava bean is. They have never been to Carmel Valley, or Carmel. A lot of them have never left New York State. Many of them are overweight, badly dressed, tattooed, dragging around kids, wearing camo, driving rusty trucks. They are also, for my money, the best human beings on the planet — the kindest, most patient, hardworking, decent people I’ve ever had the privilege to be associated with. And they shop at Wal-Mart.

Am I romanticizing? Probably. Are they all good people — of course not. But I know that I would much, much, much rather hear some guy buying beer and a grinding wheel at Wal-Mart tell me about how the driveshaft on his truck broke and the mechanic in Horseheads ripped him off (this really happened during my shopping spree) than listen to a fava bean grower in Carmel Valley wearing a $300 Patagonia pullover talk about gluten.

If you shop at the Gang Mills Wal-Mart, you don’t know, or care, about DEI, the patriarchy, organic veggies or AI. You need diapers, milk and bootlaces. You don’t have any money to spare. And if you can avoid it, you also don’t want to drive all over Steuben County getting this stuff. You want to get it all in one place, cheaply. Hence, Wal-Mart.

One of the arguments against Wal-Mart, of course, is that they’ve pulverized a lot of small businesses. To some extent this is true. It’s been years, decades since I’ve seen, for example, a small, local sporting-goods store that wasn’t fighting to stay alive. Or already dead. But let’s take a closer look at this, shall we?

When I was in high school, the place to go was Henyan’s Sporting Goods, on Market Street. Doug Henyan ran the place, owned it, and was the quintessential small-town merchant. Friendly, reasonable, he tended to stock stuff for the local market — hunting supplies, football, basketball, baseball stuff. That was pretty much it. He was a nice man. My brother set some kind of record for lettering in every sport imaginable in high school, so we were Doug’s store a LOT. The place has been gone for decades, and in some kind of landmark turn of events, has been reduced to a Cute Small Town Christmas ornament you can buy on eBay. Seeing your childhood sporting goods store recreated as that is a weird experience.

And yet. If you needed something unusual, even slightly unusual, Doug wouldn’t have it. He’d have to order it — you’d have to wait weeks. His store wasn’t cheap — he had a family to feed, and everything was full price. He was closed evenings, and weekends, and holidays. And if you needed, say, a basketball, you had to drive to Market Street to get it from Doug, then you’d have to drive to the Building Company for rock salt, then you’d have to drive to the Food Mart for your groceries, then drive home. Or whatever. This took hours, and was worse in the rain or snow or whatever. Getting four things would take hours, and miles.

Now, you can get all that stuff at Wal-Mart. The real human beings who spend their money on stuff, as nice as people like Doug Henyan were, still want to save money and time. So they go to Wal-Mart. People who criticize Wal-Mart often ignore the actual customers.

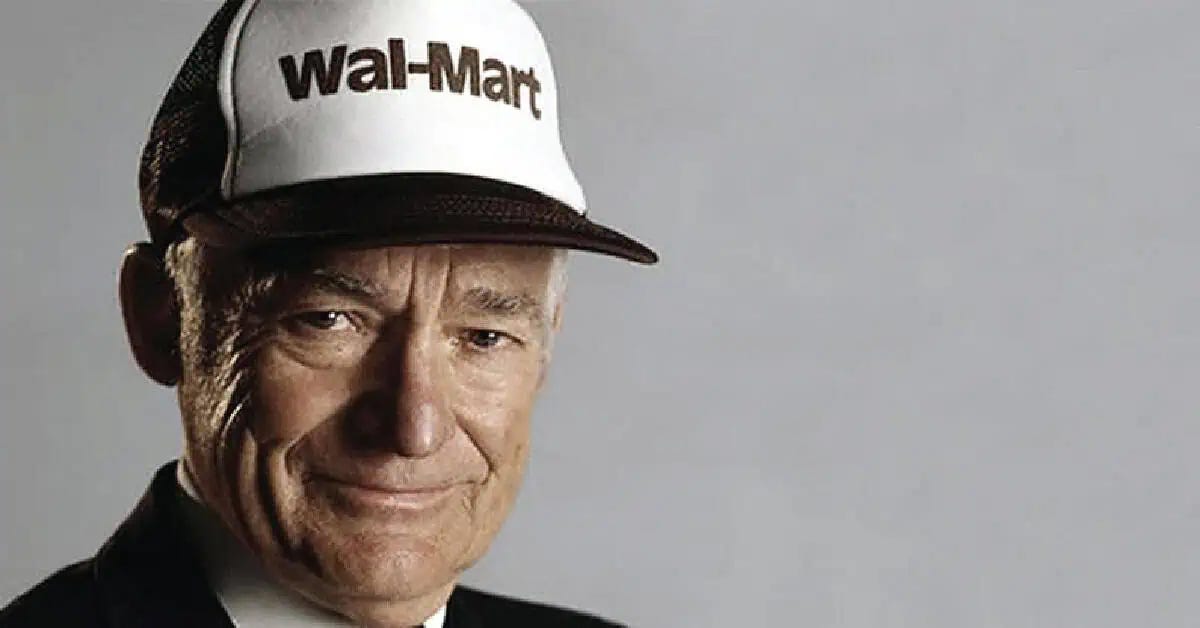

And customers were the obsession of Wal-Mart’s founder, Sam Walton. I am a huge fan of the man, despite never having met him. I read his book — he’s nobody’s idea of a great writer, but the story is extraordinary. Sam Walton was a tall, good-looking small-town boy who was insanely competitive, all about results, and completely, utterly, totally disconnected from the the networking, the climbing, the social and political and cultural maneuvering that is so prominent in businesses as I’ve seen it. He had, for instance, absolutely no problem wearing a cheap, foam Wal-Mart hat with a business suit. He did it a lot. Imagine Tim Cook wearing an Apple hat.

In fact, Apple, where I worked for three years, was the cultural opposite of Wal-Mart. Everybody I worked with was so professional they gleamed. I never saw anyone overweight, or emotional, or say anything that didn’t sound both casual and smart. Communication was done with the most subtle, delicate variations in language for emphasis and meaning.

My favorite of all the Gleaming Apple People was my producer, James. James’s job was to make sure the trains ran on time, which required unbelievable organizational skills, an iron tolerance for meetings and incredible diplomacy. James could make the very direct point that one was late with work which was badly needed with the most careful, polished language imaginable. He’d spank you, and you’d only realize much later that your bottom was sore.

Sam Walton wasn’t that. He was a guy who was a merchant, first, last and essentially. The book talks about him figuring out the best way, in his first stores, to display watermelons (which exploded in the Arkansas heat), women’s panties, brooms. He drove a pickup truck, went to church, loved hunting and dogs, and wore suits from Wal-Mart for his entire life. One of Tim Cook’s shirts probably cost more than one of Sam Walton’s suits. And Walton was totally comfortable with all of these things. His children are the richest people on the planet now. His family, which is intact, thank you very much, owns 50% of the stock in the company, with a collective net worth of around $400 billion.

And Sam Walton said one of the most brilliant things I’ve ever read about business, which also seems obvious, which is true of a lot of wisdom:

There is only one boss: the customer. And he can fire everyone in the company, from the chairman on down, simply by spending his money somewhere else.

Which brings us back to Wal-Mart’s customers. I was standing in line at the guns and ammunition counter in the Gang Mills Wal-Mart, because they also handled optics and I needed a pair of binoculars. The people ahead of me were talking to the clerk, who must have weighed at least 400 pounds, about what one cuts moonshine with to hide the awful taste. After a minute of this, the woman ahead of me simply said, “Shit, I don’t do any of that. I just drink it straight.” I smiled, and said, “My kind of girl.” Everyone laughed. I meant it.

I think, in the end, that a lot of the hostility that’s directed at Wal-Mart isn’t about the social issues, or labor practices, or the demise of small businesses. I really don’t. I think it’s about class.

Culturally, socially, politically, people who wear trucker hats and drink Coors Light are utterly alien to the people in this country who usually run things. I was talking to a friend in California — a surpassingly decent, kind, sensitive, educated person — who literally didn’t know what Carhartts were. NB: I’m wearing some as I type this.

This cultural gulf was beautifully expressed in an old episode of The West Wing, where the White House staff was arguing about the Second Amendment:

Sam Seaborn: It's not about personal freedom, and it certainly has nothing to do with public safety. It's just that some people like guns.

Ainsley Hayes: Yes, they do. But you know what's more insidious than that? Your gun control position doesn't have anything to do with public safety, and it's certainly not about personal freedom. It's about you don't like people who *do* like guns. You don't like the people.

I do like the people. I like them a lot. I cherish walking through Wal-Mart and being instantly accepted at face value by people who by and large could not imagine judging anyone. Who will instantly drop what they’re doing and help you if you need it. Who just want to be able to pick up eggs and a frying pan and get home without the damn truck breaking down. I don’t care who they vote for or sleep with or whether they’ve read Stendhal or The New Yorker.

I just like them.

Peter you hit a sweet spot with this story. Thank you

Got me thinking ... about the strange bubble that is Silicon Valley. I appreciate your writing and stories.