One of the many wonderful things about my ex-girlfriend Freya, was the absolutely unique and endlessly interesting way she used language. As an example, she just loved gendered nouns, and would often add “lady” as a prefix to words to indicate that they were for feminine objects or pursuits. For instance, she carried a ladypurse. When she went on a roadtrip to figure some things out about her life, it was a ladyquest. And when I met her, she was living in an absolutely gorgeous cabin overlooking Carmel Valley, California. It was known, of course, as the “ladycabin”.

So, I’m going to do the same thing. In manworld, there are certain guys who are sort of shamans. They have magical abilities at some activity that has spiritual meaning to men. Or, less breathlessly, they’re really, really good at things men find significant, and this gives them special standing. On some very deep level, standing next to a guy like this is like standing next to Luke Skywalker. They look like you, but they have mastered some version of The Force.

One example is the card-counter. I worked for a couple of years with a fellow who was a professional poker player in Las Vegas, before getting a Wharton MBA, founding a couple of startups and making himself rich. He always had this magical aura about him due to his seemingly supernatural skills at gambling. My father was the same thing. A surgeon is the guy who steps in when things are really, really bad, and can literally save your life. Other men think of them differently.

Another example is the fly fishing guide. This is a guy who has made a profession, a career, out of the supremely complex, demanding, fascinating sport of fly fishing. He knows things you don’t. He does things you can’t. When the game is the ancient male sport of contending with nature and (in extreme theory) bringing home sustenance for the tribe, an expert guide is special in a way that’s almost mystical. And for me, fishing with a really good guide is a master class in a dozen things at once, and an exposure to the special, quasi-magical juju he radiates.

Like Joe Cauvell, who I spent a day with last month on Willowemoc Creek.

I wrote about him in a previous Substack. That day was with Freya, so she, as a beginner, got about 2/3 of his attention. It was still an absolutely magical day. I caught a trout, which to any real fly fisherperson, is beside the point. This time, I had Joe all to myself for the entire day, and it was magical again. Just a different kind of magic — it was teaching magic, if you like.

I did not, however, catch a fish. Let’s get that out of the way right here and now. It’s not like I’m defensive about it or embarrassed or anything. I didn’t catch a fish, okay? What I did do, which is perhaps more valuable, is learn.

I’m a big fan of learning things. I have spent a LOT of time, and considerable expense, as a student, being taught by all kinds of people. This has included golf pros, coaches of all kinds (including the mighty Kevin Carter, my first trainer), therapists and shrinks and law professors, including Elizabeth Warren, by the way. Last night, I began to learn CrossFit from Melissa Alford and Neil Jones, of Funny Farm Fitness, which is a lot more hardcore than the silly name would make it seem.

Being a student is something only humans can do, and it’s an absolutely amazing activity, and a privilege. Think about it: you can work one-on-one with someone who has expertise, and they will share it with you. It’s incredible to me, still, that I can attempt to perform, say, a reverse lunge and someone can stand and watch, and tell me, then and there, how to do it better. Koda has to learn everything the hard way. Because I’m human, I get to have teachers. What an incredible blessing.

A great teacher not only dazzles you with what they know and can do, but makes it seem possible that one day, you could know and do the same things. And they make you want to. I will never deadlift 500 pounds. I will never comment meaningfully on the Torah. I will never be a real gourmet chef. I simply don’t have what it takes to do any of those things, and never will. But Joe reminded me that if I put in the time and effort, I could be a really, really good fly fisherman. He did it by showing me what that meant.

We met at 10 AM, at the Roscoe Diner, in beautiful Roscoe, New York. We ate a bunch of food, talked, and mapped out the day. I had initially thought that fishing the Neversink would be a good idea, but the place I’d thought to do it required a couple of hours of difficult hiking in and out, which Joe described as “real leg-burners”. I thought better of my plan. Instead, we went to Willowemoc Creek.

We drove to the creek, rigged up, clambered down the bank, and waded in. With no distractions and nothing else to occupy his attention, Joe trained his fly-fishing guns directly on me and started teaching. “Drinking from a firehose” does not begin to describe the experience.

The creek, our classroom, is a tributary of the Delaware River. It’s famous trout water. Along with trout, it’s inhabited by eagles, osprey, beaver, otter and all kinds of other wildlife. It’s also, needless to say, beautiful. The creek is really a small river, and in order to fish it properly, the first thing you need to do is read it. “Reading” means looking at it, analyzing what you’re seeing, and figuring out where the trout are likely to be lurking. This is a much, more complex undertaking than it seems.

There are all kinds of factors to evaluate. How deep is the water, where? What kind of light is there? How fast is it moving? What time of day is it? Are there insects around — trout snacks. What kind? How many? Is the water warm or cool? The air — warm or cool? And so on and so on and so on. Joe walked me (literally) through all of this, and showed me a seam he thought we should fish: a place in the stream where the depth, current and light were right for trout to be feeding.

The entire point of fly fishing is to completely blend into the environment, and in so doing, fool a trout into thinking that a small fly made of feathers and fur (but concealing a hook) is actually the particular insect (or smaller fish) they want to eat at that moment. Trout are very finicky and smart — their discernment is backed up by millions of years of evolution. To trick them you have to get everything, to quote Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead, just exactly perfect. Hoping you’ll happen to encounter a dumb trout is a very weak strategy.

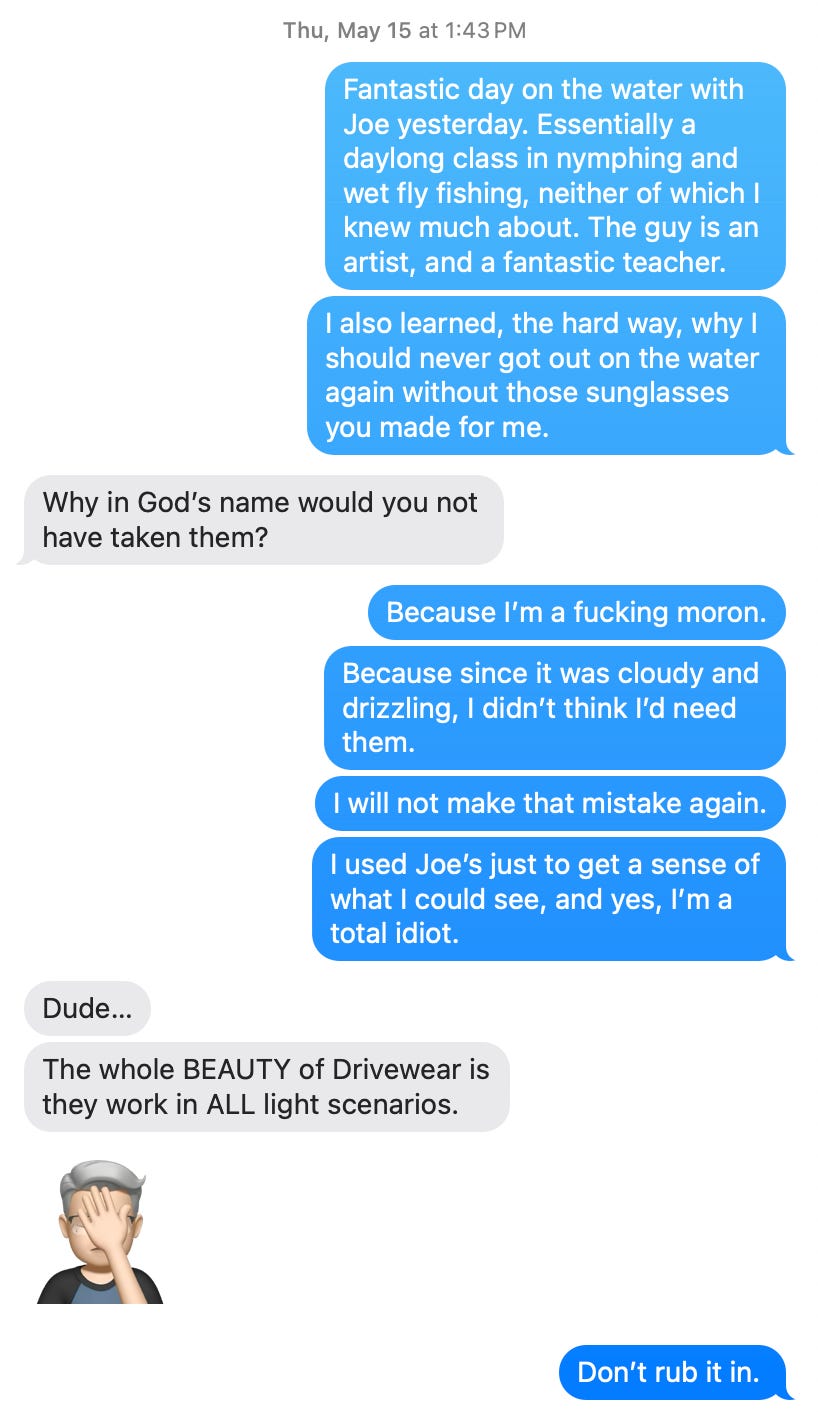

Before proceeding any further with this narrative, a confession. My pal Marty Ennulat, who is perhaps the finest optician I’ve ever worked with — and since I have miserable eyesight, I’ve worked with a LOT of them — custom-made me a pair of polarized sunglasses specifically so I could see into streams and read rivers. Marty is a fly fisherman too. They weren’t cheap — they’re really good glasses.

And I forgot them. Worse, I told Marty about this. One of my strengths is that when I do something stupid, I immediately fess up, which I did with Marty. The sheer idiocy of this move hurt his heart, I think. I don’t deserve to have him as a friend. I really do not.

Back to fishing.

Along with being endlessly patient, friendly and cheerful — and this is a guy who’s been out on the water with some real lulus, I’m sure — Joe also has a Rubik’s Cube of a mind, which he applies to chasing trout. He knows everything. About everything. Standing in a stream with him and asking questions was like going into a casino, and having every slot machine, every time, produce a huge jackpot.

The day was devoted to practicing two forms of fly fishing which were new to me — nymphing, and using wet flies. Both of these techniques are a lot more complicated than classic dry fly fishing, and to my surprise and delight, they worked. They involve tying on more than one fly, suspending them in the water rather than on it, and using specialized casting techniques to put them in the right place. I would carefully fish a seam using classic dry flies, which float on top of the water, and get totally skunked. Then, with a LOT of help from Joe, I’d fish the same seam again with wets, and get a hit about every twenty minutes.

One of these hits was big — a large, powerful trout. One second I’m minding my own business, patiently covering a seam and then, suddenly, I’ve got what feels like fucking whale on the line. I don’t freak out. I don’t do anything stupid. I keep tension on the line, do a good job of working the fish, and thirty seconds later he’s gone, and I’m standing there with a broken leader, no trout, and a bunch of questions. It was like the scene in the old Westerns where the guy is sitting in the dusty main street of the town while the horse that just threw him gallops away. Except instead of cowboy boots and a cowboy hat, I’m wearing a pair of Simms waders and a trucker hat that says “Corralitos Feed and Pet Supplies, Inc.” on it.

One of the unwritten laws of fly fishing is that you may be wearing and using thousands of dollars worth of gear, but you have to wear a hat that looks like your dog found it. Which, in this case, he did. My favorite fishing hat is one that Koda literally found while hiking. He came trotting up to me with it in his mouth, and I, uh, took possession of it.

Evidently this was not this trout’s first rodeo. What he did as soon as he realized he was hooked was to head straight for the bottom, find a convenient rock, and break the line against it. Trout:1. Peter: 0. So standing there, kind of puzzled, I ask Joe what the hell just happened. Did I do anything wrong? Could I have played him differently?

I remember a description once in The Right Stuff of what it was like to talk to Neil Armstrong. According to Wolfe, you would ask Armstrong a question, and for a moment, he wouldn’t respond. You would think he hadn’t heard. Then, he would click into action, and out would come a series of perfectly formed sentences that totally answered the question.

Joe is like that. When you’re trying to learn something, sometimes you have to extract the information you need from someone who isn’t especially good at communicating. Other times, you are dealing with someone like Joe. First, he assured me that I hadn’t done anything wrong, that the trout was just smart and experienced and that’s the way these things go sometimes. Then, he took me through an explanation of how, had I had a few more minutes, I should have properly played this fish, involving working him upstream while wading down so eventually I was holding him perpendicular to the current, which would tire him out faster because more of his surface was exposed to the moving water, thus requiring more effort from him.

The day, the lesson, went on. We spent the entire day on a stretch of water no more than 200 yards long. We switched back and forth from dry flies to wets, with Joe watching everything I did and issuing a steady stream of observations and corrections. Like Freya, he enjoyed invented his own charming language. For instance, I tend to be too gentle with my casts. Joe would see this and say, “Put a little more pepper in the recipe”, meaning “cast harder.” Another favorite term was “in the sauce” as in “That cast was right in the sauce” meaning in exactly the right place to attract trout.

Eventually, the rain began, it started to get dark, and I called it. We drove back to the diner, had a spectacularly mediocre dinner in an Italian place in Roscoe, shook hands and parted. I drove home in a pounding rainstorm, flashers blinking, left all my gear in the car, let myself in, let Koda out, and went to sleep.

Days on the water fly fishing come in all shapes and sizes. Sometimes they’re pure exhilaration. Sometimes they just suck — it’s cold, you're hung over or heartbroken and you catch nothing. And sometimes, if and when you’re lucky, you spend the day learning.

And I’ve signed up for three more days with Joe.

I'm very glad you have booked three more days with him. Then do more. You deserve it.