Twenty-six or so years ago, while in the employ of an exceptionally ruthless lawyer named Dick Sprague, I sat at a little table in the food court of Liberty Place in Philadelphia, and listened to a guy tell me a story. The story was of something called a startup, in far-off California. It was going to be based on something called the Internet, was going to involve advertising somehow, and in the end, we were all going to make an enormous amount of money. I listened. I believed him. And I went to California.

And unlike in those old episodes of The Honeymooners, where Ralph Kramden invests in yet another crazy scheme that blows up in his dumb face, this one worked. The timing was perfect. The team was amazing. The company was sold, then taken public. And I, along with all of my beloved colleagues did, in fact, make a great deal of money. It was glamorous, exciting, important, risky, and most of all, it was successful. One of my fondest memories is of standing on a filing cabinet, drunk on champagne, and watching the stock in our new baby, Flycast Communications, begin trading on the NASDAQ.

Now, many years later, with a long string of experiences behind me, I’ve packed up, left California, driven across the continent with Koda, and returned to the little town I came from: Corning, New York.

Along the way, Koda decided to eat part of the back seat of the car to punish me for taking too long at lunch while he waited. I’m not sure how to feel about this. But here I am.

I woke up this morning in an apartment in a three-story brick building that’s a century old. It was once my junior high school. I literally took social studies, algebra, history right here. The bricks it’s made of were manufactured here. The men who built it were Irish and Italian immigrants. I went to school with their grandchildren. I know every foot of this place. I was born about a hundred yards from where I’m sitting and typing this, in a hospital where my father practiced surgery for forty years. If home exists anywhere for anyone, it’s here, for me.

I’m not exactly sure why I came back. I just knew it was time. And now, every once in a while, I pause, and experience this solid, right, sensation. I am home.

Part of it, of course, is family. My parents are both dead – I visited their graves on the last day of my drive. My daughters are all on the East Coast. For many brave and energetic years, that didn’t really matter to me. But now, at 62, with the finish line of my life in sight, if not at hand, it does matter. I want to be near them. The ancient need to draw closer to one’s kin is strengthening.

Another part, perhaps a more important one, is that despite trying and trying and trying, California never really finally clicked into place as home for me. This isn’t anyone’s fault, and especially not California’s. As one of my daughters said when I broke the news, “You love California!” I do. But not quite enough, perhaps. Or not as much as I love them.

I went everywhere in the state, from San Diego to Mount Shasta to the Sierras to Mendocino. I had children there, made and spent a lot of money, made memories, lived in several different places, and encountered everyone from hippies to technology executives to ranchers, farmers, Mexicans, Asians. Like countless other people, I contributed a tiny piece of myself to the amazing, ongoing story that is San Francisco.

And yet, at the most basic level, California never quite made sense to me. And making sense, fitting into how I understand being alive in this world, is more and more important.

I remember when I first moved there, I was still married, and my oldest was a toddler. On the very first family visit, I front-loaded the experience from California by having everyone stay at the Hotel Huntington on Nob Hill, a gorgeous, very expensive five-star boutique hotel that sadly was taken out by COVID.

Later, we went on a family camping trip to the Marin Headlands. I got up in the morning to brew coffee and take in the jaw-dropping view of the Golden Gate and the city. Next to us, in the adjacent camping spot, was a young woman who had just exited her tent to walk down the hill, catch a bus across into San Francisco, and find a job. I loved that. It was so cool. I wanted more of that kind of life.

And yet, underneath, or maybe next to, all the wonder, I also found a kind of menace in California. There’s a low hum of instability, a constant sense that the place exists due to a lot of willingness to play the odds, and you just might lose. I knew people who, as the song goes, sank into their dreams, and suffered horribly for it. Sometimes it killed them. In California, it always feels a little unsteady. You can never really take your eye off the ball there. At least I couldn’t.

As the ultimate tangible metaphor for this, the earth itself isn’t stable. Earthquakes are a fact of life in California. The first time you feel the actual ground moving under your feet is a real shock. “Wait, the ground is moving?”

Much of the place is also naturally arid to the point of being uninhabitable, and can be lived in because of one of the world’s biggest water management systems. There is no rain at all – like, zero – in the summer. Everything turns brown and dusty and dry. There is nothing so dry as the ground in California in late summer. It’s like talcum powder. Around about Halloween, the rains come, and much of that ground will turn to mud. Stretches of Route 1, the legendary Pacific Coast Highway, are routinely washed into the ocean. Incredibly beautiful, but you can’t count on it being there.

In the mountains, conversely, the snow caused by these same rains can be terrifyingly deep – twenty, thirty feet. Huge storms, or atmospheric rivers, slam into the granite of the western side of the Sierras, and dump everything they’re carrying. If you’re caught in that and unlucky, you’re dead. See Donner Party. When that melts, it’s stored in gigantic reservoirs, then piped to where it’s needed. The entire state depends on this plumbing project. It’s unreal to me, and disorienting, that Los Angeles can exist due to huge pipes.

In the summer, the state is sometimes wracked by fires on a scale that you cannot believe until you experience it. During fire season, it is so dry that the merest spark can cause the whole place to explode. When I lived in Santa Cruz, the county experienced the CZU Complex fire, which eventually torched 85,000 acres. For perspective, that’s Manhattan burning to the ground, all of it — four times. That happens fairly often. One-quarter of Santa Cruz county was reduced to ash. The sun was blotted out with a sickening greenish-gray layer of smoke. Ash was on everything. It was genuinely apocalyptic. In some parts of the state, it’s literally impossible to buy fire insurance.

The counterbalance to this sense of instability is a kind of dreamy, sparkly sense of opportunity that exists nowhere else in the world. Fantasies are actually manufactured in California, and they really do come true, for better or worse. People walk around with their imaginations, their desires, lit up and shining around them, like a cloud of fireflies. I had a friend remark once that in Santa Cruz, we saw things every day that people in other parts of the country spend years saving up to experience. She was right.

For instance, outside Santa Cruz is a Buddhist retreat center, the Land of Medicine Buddha. In the middle of the redwoods, a bunch of people have created a kind of Buddhist resort. You walk through the trees, and there are stupa, quotations from ancient Buddhist texts, temple bells. The state was created by explorers, loggers, miners. The land the center sits on used to be owned by a family that drilled for oil there. No matter. If you want to try something, California smiles encouragingly and says, “Sure.”

This unreality is enhanced by the fact that California is really two states. If you don’t live there, you don’t know this. The parts near the coast are expensive, beautiful, cool in the summer and temperate in the winter. Eating dinner outdoors in Montecito is kind of like a little visit to heaven. It feels friendly, and civilized, and elegant and wise and clean. Coastal California is the part tourists visit and take pictures of. It’s ferociously expensive, and so beautiful in places that your heart stops. Big Sur is an example. This is the California they make movies about.

However, you go inland, and it’s completely different. There’s a lot of poverty. There’re gangs and graffiti and industrial agriculture that makes the landscape incredibly ugly. You can drive down a country highway in, say, Salinas and see acre after acre of grimy plastic sheeting shielding, I think, strawberries, which will eventually be picked by migrant laborers who are given plastic porta-potties in the middle of the field to relieve themselves. It’s called “plasticulture”. No tourists go to Turlock.

So, here I am, having traveled all the way across the country to return to my home. Thomas Wolfe had something to say about this. He thinks I’m deluded:

You can't go back home to your family, back home to your childhood, back home to romantic love, back home to a young man's dreams of glory and of fame, back home to exile, to escape to Europe and some foreign land, back home to lyricism, to singing just for singing's sake, back home to aestheticism, to one's youthful idea of 'the artist' and the all-sufficiency of 'art' and 'beauty' and 'love,' back home to the ivory tower, back home to places in the country, to the cottage in Bermude, away from all the strife and conflict of the world, back home to the father you have lost and have been looking for, back home to someone who can help you, save you, ease the burden for you, back home to the old forms and systems of things which once seemed everlasting but which are changing all the time--back home to the escapes of Time and Memory.

I think he’s wrong. I’m here to revisit my beginnings, in a way, and to see, as an adult, what they have to teach me. I’m not looking for an escape, but a path forward.

I’ve only been here a couple of weeks, but I have seen, I think, glimmers of what this adds up to. While the memories are still all around me, Corning has changed and so have I. It’s still a factory town, still a small town. On a Saturday night, I could hear the roar of the high school football game crowd in the valley below me, in the same stadium I used to attend games at. I go out at night to walk Koda and smell woodsmoke in the air – people heat their houses with woodstoves. The factory whistle still blows morning, noon and night.

Yet, I can also walk down to Market Street, and find bars and restaurants that would not be out of place in San Francisco. Open late, great food, interesting music. I now notice how beautiful and elegant the houses in my little neighborhood are. Pretty much anything I need or want can now either be delivered, downloaded or driven to, easily, whether it’s a deer rifle, good Brie or a set of bookshelves. None of this was either around or noticeable when I was growing up here – I was too preoccupied with getting to second base with Becca Truax. And, of course, the Internet didn’t exist.

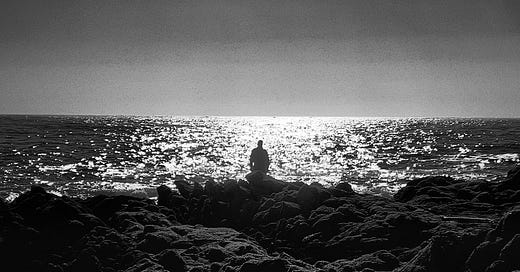

I came back because on some very basic level, I feel like I want to learn who I am. And whenever I think of who I am, I think of where I’m from. I want to see the rivers, the rolling hills, the quiet and isolation I grew up with, and that are such a deep part of my memories and identity that it’s hard to separate myself from that sense of place.

I want to revisit the memories, impressions and ideas of my childhood, and see what, if anything, is still there, has endured. In some ways, of course, I’m a completely different person. But in other ways, I suspect I may be the exact same as I was when I was eight. I want to find out.

I want to be with the people I grew up with again. I remember visiting a friend in downtown Carmel, California. Carmel is sort of like Disneyland for very, very rich people. The average price of a home there is $3.3 million. Here in Corning, it’s $175,000.

He was on his second marriage to a much younger woman who looked like a model, had a baby daughter at the age of 50 or so and probably paid $10,000 a month in rent for his house. He invested in technology companies. I liked him a lot, but at the most basic level, nothing about his life made sense to me.

This morning, I took Koda on a very long walk, through mud and snow, on West Hill Road, in the town of Hornby, New York, population 1,607. Along the way, I saw a wall. The wall, and thousands and thousands like it, was carefully constructed over a century or so, of slate stones pulled one by one out of the field next to it during plowing. The amount of labor, persistence and effort that field, that farmer, and that wall, manifest inspires and grounds me. And makes sense to me.

This wall was built by a real person, using his body as if he were a draft animal, to survive in an isolated, beautiful, hard place, where the wind feels like you’re being hit in the face. On a cloudy day in November, the countryside is dark, forbidding, and to me, beautiful. Compared to that, Big Sur seems to me like cotton candy left out in the rain.

When I was younger, I always believed that when I was in my sixties, I’d be safely and securely married, a father, settled down, comfortable and content. Not quite. I’m definitely a father. But I haven’t settled down, I’m not content (yet) and I want to see what happens if I deliberately construct the next part of my life completely on my own terms. I’m hoping it will be familiar, deeply satisfying, and feel like home should. I’m still looking for something, and right now it’s not in California.

I have managed to write this Substack for a year without quoting Thoreau, who I worship. Enough of that. Here’s what he said about what I’m trying to do in, of course, Walden:

My instinct tells me that my head is an organ for burrowing, as some creatures use their snout and fore-paws, and with it I would mine and burrow my way through these hills. I think that the richest vein is somewhere hereabouts; so by the divining rod and thin rising vapors I judge; and here I will begin to mine.

Time to start digging. I’ll let you know what I find.

Great piece. It made me reflect on how I think of unstable ground and a continuous housing crisis as "home" and any city with hundred-year-old walls as foreign.

To wander, to live with intention. To laugh and to learn. May you find peace